This past January, the administration at Lincoln Elementary School in Richmond, led by Principal Taylor Parham, made a bold mid-year shift: implementing the “Walk to Read” model, a targeted literacy intervention designed to accelerate reading proficiency for all students.

Lincoln’s team acted with urgency and went for it. They were inspired by the success of nearby Nystrom Elementary, which first implemented the Walk to Read model four years earlier.

“Reading is the most important thing we do in elementary school; it affects all subjects,” Principal Parham said. “We could have said ‘let’s wait until August,’ but this impacts kids’ lives and their future.”

Walk to Read fundamentally reshapes reading instruction by meeting students exactly where they are and driving towards progress. “It’s an all-hands-on-deck model,” said Lani Mednick, Implementation Manager at CORE Learning, which partnered with Lincoln through Chamberlin Education Foundation support.

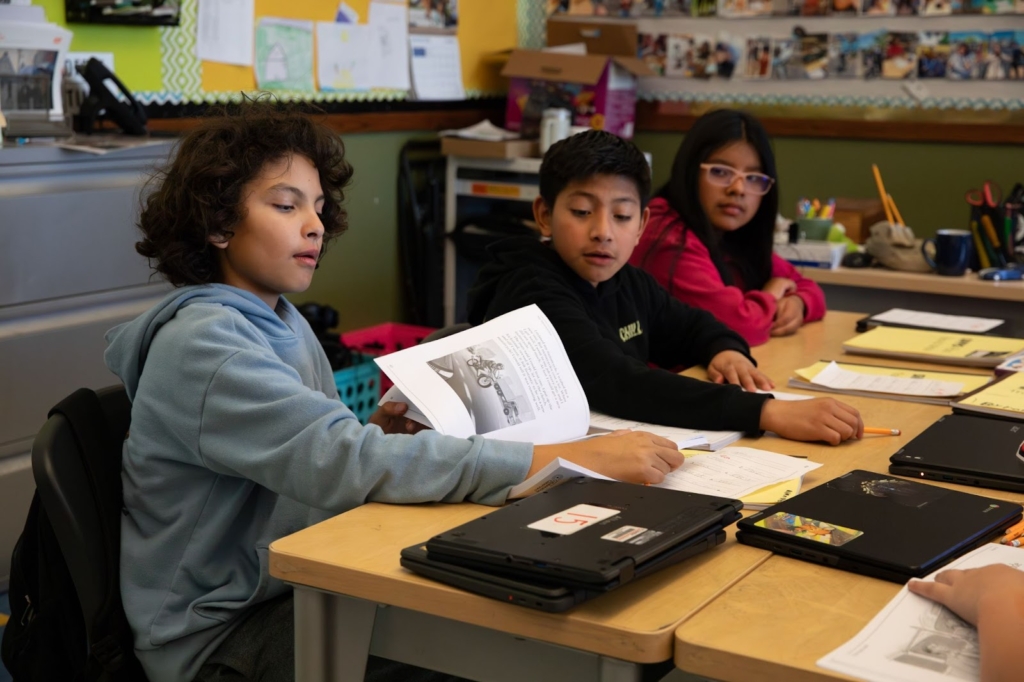

Students work with peers at similar reading levels, not just their same-grade classmates, allowing teachers to focus on exactly what each group needs to learn and accelerate learning rapidly for that group. The Walk to Read model uses differentiated instruction by having students literally walk from their normal classroom to differentiated groups during their reading block, often using the SIPPS (Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics, and Sight Words) program as the structured literacy curriculum for foundational literacy skills.

For example, a third grader can have a reading gap addressed by working in a small group focused on decoding skills, while another third grader on grade level works in a small-group book club for advanced readers called ‘novel studies.’ The groups are fluid and adjusted every few weeks based on assessment results.

“Students go through a clear scope and sequence and nothing is left to chance,” Mednick said. “They get all of their unfinished learning needs filled.”

Implementing Walk to Read required a cultural shift at the school, especially for teachers. The new model dismantles silos, making literacy instruction a shared responsibility for all educators.

Pilar Alvarado, the upper-grade literacy lead at Lincoln, said there was some initial hesitation from teachers because they were concerned about how this new model would function, especially for special education students and English Language Learner students. That changed when the fifth and sixth grades successfully moved forward with it and students quickly made strides.

“Teachers are now saying, ‘Next year I want to lead novel studies’ or ‘I want to teach lessons 1–20,’” she said. “They’re getting invested.”

In grades K-2 at Lincoln, Literacy Coach Key-aira Scott provides targeted reading intervention by pulling small groups while classroom teachers provide intervention, as well.

“The success of that K-2 foundational work has helped support the implementation of Walk to Read in grades 3-6,” Principal Parham said.

There has been visible progress, like the school starting with two full classrooms of 5th and 6th graders at a lower level, and then so many students advancing that Alvarado said she had to start a novel study group.

Other early signs are also promising, such as i-Ready gains and improved confidence among English Language Learners (Alvarado noted seeing ELL students having full conversations in English). Lincoln’s team also acknowledged that their data systems are still evolving.

“We’ve learned a lot,” said Principal Parham, noting plans to create stronger systems for capturing data next year.

Alvarado said she especially noticed how Walk to Read is impacting students in Special Education. She remembers special education students cheering when they moved up a level to a new group.

“Their confidence grew so much,” she said. “Two moved up to the next group, and they couldn’t even believe it. Now they volunteer to read aloud even if they’ll make mistakes.”

The Lincoln students have become Walk to Read’s biggest fans. “They ask me every single day: ‘Do we have SIPPS today?’” Alvarado said, laughing.

Even reluctant readers now volunteer to sound out words publicly. “Kids who used to hide during reading time now correct us on phonics rules,” Principal Parham said.

Beyond academic growth, Walk to Read has helped strengthen Lincoln’s culture of connection. Because students interact with multiple teachers across groups, they build trusted relationships with more adults. Alvarado mentioned she already knew most of her future 6th graders before they even entered her classroom.

As Lincoln plans for the next school year, the team is refining its approach as they use data more intentionally to drive groupings and instruction.

The success so far has proven to Principal Parham that making a midyear shift to Walk to Read was worth it. “We’re seeing kids taking risks in English who never would before,” she said. “That dramatic shift showed us we couldn’t wait.”

Mednick said she’s not surprised to see Walk to Read get off to such a great start at Lincoln. She knows it’s a proven strategy because she’s seen it before.

“I’m a big fan because I’ve seen it work,” she said. “I’ve seen kids happy. I’ve seen student outcomes skyrocket and lots of growth. That’s what we want to see.”